A view of Lake Ohrid, North Macedonia.

Security is mostly a superstition. It does not exist in nature, nor do the children of men as a whole experience it. Avoiding danger is no safer in the long run than outright exposure. Life is either a daring adventure, or nothing. Helen Keller

Eschewing the gauntlet of cruise tour operators along the river, for my last day in Ohrid, I opted to hike as far as possible along the beach in the opposite direction, away from the popular old town, tourists and souvenir shops. Backpack ready, I headed south, pleased to discover the sophistication of a paved pathway affording views of the river on the right, juxtaposted with vegetable fields and farmers on the left. Having overcome my emotions towards the ubiquitous stray dogs in Macedonia, I became aware that the two dogs walking ahead of me actually looked quite healthy, like they had been fed and brushed. Fortunate to have learnt that there are some volunteer groups helping out Macedonia’s strays, I took heart that these ones may have been fortunate recipients of care and sustenance. As the paved pathway came to an end, with workmen, still paving to extend it, the dogs looked towards me and gestured towards a bush pathway. I followed, and after stepping over a small creek, ended up back on track. This navigation continued for about the next half hour with the dogs patiently waiting for me and then leading me along appropriate pathways.

Growing wild along Lake Ohrid.

Choices: fishing solitude or boat trip?

Wondering, for a moment, if they had been trained to lure naïve Australian tourists into the bush to be bludgeoned or robbed, I was relieved to find their intentions entirely altruistic. I had no food to offer, yet they were content to trot ahead of me as escorts. Eventually, they seemed to decide I could manage on my own and turned back.

From that point on, the scenery shifted from postcard-perfect lake views dotted with wildflowers to vast, eerily vacant hotels swallowed by overgrown grass, some faintly echoing the Overlook Hotel from The Shining. Although it was June, tourism still felt half-asleep. At times the silence was unlike anything I had experienced elsewhere in Ohrid, and I again felt fortunate to wander such beautiful trails without having to share them.

The ominous and seemingly isolated Hotel Filip.

River views.

Upon return, and a 35 minute walk to the bus station to facilitate my ticket to Skopje, I was reminded of another common sight in Ohrid, and I don’t mean the ubiquitous monasteries. Ohrid is full of old cars. Worn and rusty, these are still (mostly) functioning cars from the 1980s. Most are European and one noteworthy brand is the Yugo. A bit slow off the mark, I eventually realised that Yugo is short for Yugoslavia (d’uh). Apparently, they were exported to America in the 80s and one could acquire one for just $4,000, but they were consequently snubbed as being poorly engineered and ugly. I compared our Australian standards and how easily insurance companies write off cars once it costs more than $1,000 to fix them; these ones had huge holes, rust and huge chunks of metal missing. None would pass roadworthy tests in Australia but they were still getting around.

Various old cars.

An old car next to an obsolete fast food booth.

The two dogs that guided me along my walk.

I spent five days in Ohrid, staying in a tiny home exchange apartment just above the lake. It had one memorable feature. If I wanted to heat water, I had to step out onto the balcony and use a small stove attached to a gas cylinder. It worked, but it made even a cup of tea feel like a mini expedition.

Most days began with a walk along Lake Ohrid. The lakeside path is easy and scenic, and the water is so clear you can see the stones beneath the surface. From there, it was simple to continue into the old town and explore at a relaxed pace.

Simple living from my Home Exchange apartment.

I visited Samuel’s Fortress, which sits on one of the higher points above the city. The uphill walk was steady but manageable, and the view from the top was worth it. You get a full sweep of the old town, the red roofs, and the wide stretch of the lake toward Albania. Samuel’s Fortress sits on the highest point above Ohrid and dates back to the time of Tsar Samuel in the late 10th and early 11th centuries. What you see today is a mix of original medieval walls and later restorations, but the scale still gives a good sense of how powerful the stronghold once was. The hilltop is mostly taken up by the fortress itself, though there is also a small residential flat tucked near the top, which always looks slightly out of place beside the heavy stone ramparts.

Views of and from Samuel’s Fortress.

One of the main drawcards of Ohrid is its Monastery of Saint Naum on the southern shore. Founded in 905, it is an important site for North Macedonia and a major attraction for visitors. The monastery has distinctive Byzantine architecture, a green-domed church rebuilt in the 16th century, and the tomb of Saint Naum inside. The gardens and springs around the complex make the area feel calm and spacious, and the peacocks wandering around add a slightly surreal touch.

Monastery of Saint Naum.

I also visited the Clock Tower, which dates from 1726 and is a monument from the Ottoman period. It sits a little further uphill from the church of St Bogorodica Kamenska, close to Krusevska Republika Square, the one with the 900 year old Cinar plane tree and the fountain. From the tower, I followed the road uphill and eventually reached the Upper Gate.

Views of the 1726 Clock Tower.

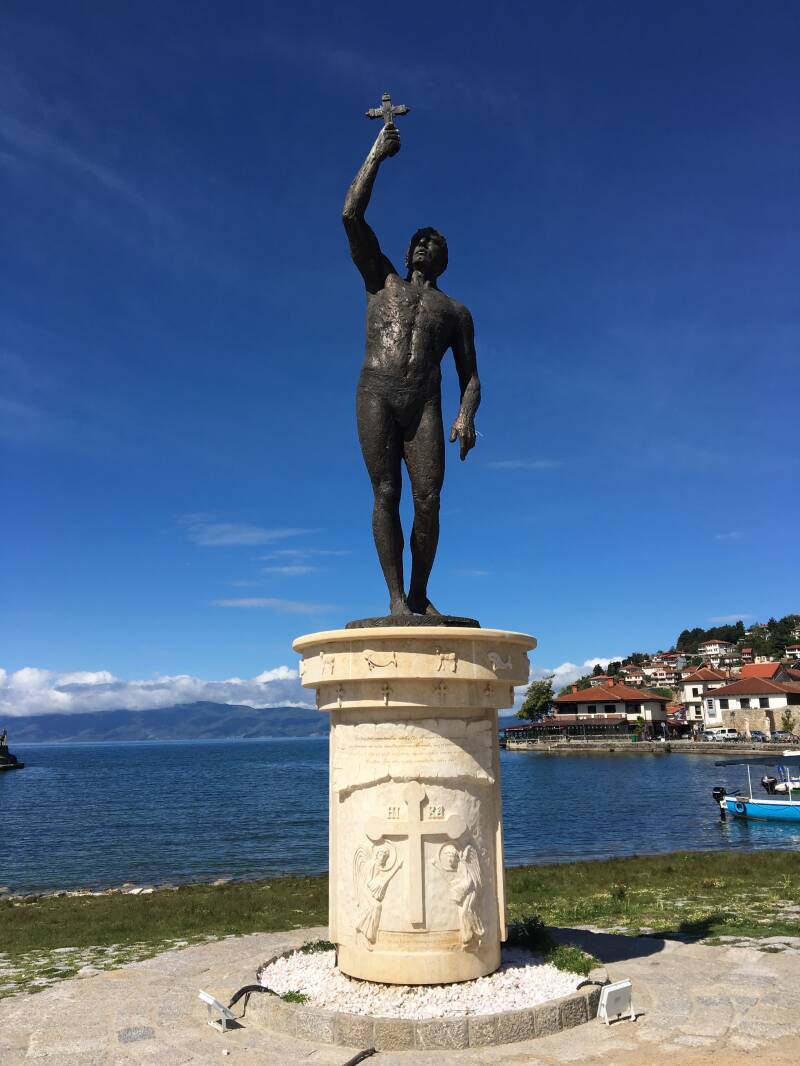

It is hard to miss the Epiphany Monument on the lakefront. It marks the annual Orthodox Epiphany celebration, when swimmers dive into the icy water to retrieve a wooden cross thrown by a priest. Standing there, it was easy to picture the crowds that gather each January, the ceremony unfolding against the backdrop of the lake.

The Epiphany Monument.

I visited the Roman Amphitheatre too, tucked into the old town below the fortress. Built in the 2nd century BC, it is the only surviving Hellenistic era theatre in North Macedonia. It’s partly restored, but when I wandered through it the only occupants were a few stray dogs stretched out in the sun, giving the place a much quieter atmosphere than the crowds it once held.

The 2nd Century Roman Amphitheatre.

Woodlands near the lake.

Ohrid itself has a long history, stretching back to ancient times, and many of its churches and historic buildings reflect its role as a centre of culture and literacy. With both the city and the lake listed as UNESCO World Heritage sites, there is plenty to explore without rushing.

Five days gave me enough time to settle into the rhythm of the town, walk almost everywhere, and make simple day trips without planning too much. Between the lakeside paths, the fortress views, the historic churches, and the visit to Saint Naum, it felt like a balanced and easy introduction to one of North Macedonia’s most interesting regions.

Read about how an American nearly caused a war with Serbia through his criticism of his Yugo: https://balkaninsight.com/2011/01/22/on-hold-for-a-sec-yugo/

Beauty and intrigue comes in all forms and stimulating all senses in Ohrid.

Create Your Own Website With Webador