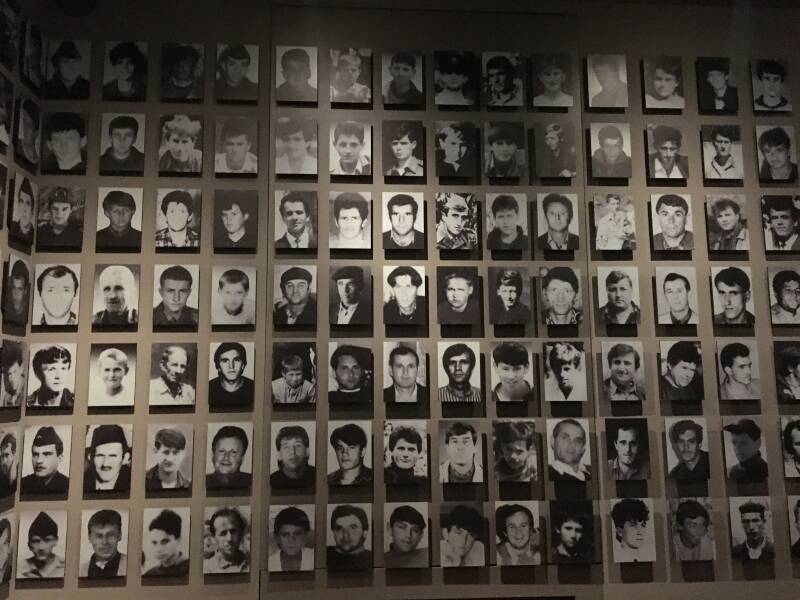

Some of the many victims of the Bosnian siege in Srebrenica.

In the 1990s, I primarily experienced Miss Sarajevo through the music, as an avid fan of the Brian Eno–Bono collaborations, including their work with the band The Passengers, rather than fully grasping the gravity of the film’s subject matter. This was one of those CDs (it was the ’90s) that I played repetitively, fascinated by how Brian Eno broke new ground by featuring Luciano Pavarotti’s operatic voice in Miss Sarajevo, instead of the more expected guitar break from Bono’s softer vocals in the ambient track.

Although the song could be interpreted as political, its lyrics are far subtler than Bono’s other war-themed songs, such as the relentless “In the Name of Love” U2 released in the ’80s. Miss Sarajevo is paradoxically quiet and soothing, masking the weight of its subject.

“Is there a time for keeping your distance

A time to turn your eyes away

Is there a time for keeping your head down

For getting on with your day”

These lines reflect the apathy of the wider world, turning a blind eye to the four years of bloodshed that unfolded in what became Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Photos from the 2019 exhibition at Gallery 11/07/95.

Bono funded the film, whose premise centers on the irony of a beauty contest held in Sarajevo during the siege, in which the participants famously held up a banner reading “Don’t kill us.” This scene is undoubtedly the focal point, yet it is the personal stories of Sarajevo’s residents at the time that I find most compelling. Perhaps the film carries a dual meaning: the interviewer frequently returns to an eternally optimistic young teenager who, along with her friends, sat in bombed-out cars singing contemporary American pop music. Only towards the end of the film do we see evidence of her transformation; time has passed, marked by longer hair and a more drawn face. “Things aren’t so good now; people are dying,” she offers, speaking alone this time, without her friends.

Another short dramatized film I watched at the gallery, Ten Minutes, made more recently, contrasts ten minutes in the life of a boy during the siege, sent out to fetch water and bread for his family, with ten minutes in the day of a tourist in Rome getting a film processed (set in the ’90s, pre-digital age). At the risk of racial stereotyping (the tourist is Japanese), I found the film effective in confronting viewers with the unfair circumstances some people face, without over-dramatizing or hammering the point. I have deliberately avoided spoilers, so I recommend watching it, ideally on a large TV screen (Chromecast or HDMI cable, anyone?). I can’t wait to seek out Ahmed Imamović’s other films from this period, such as Go West.

As I walked home on a Tuesday night, I observed many locals and perhaps some tourists out and about: mostly eating gelato, drinking coffee, or shopping in designer stores. Many were well-dressed Muslims, all navigating streets lined with bullet-scarred buildings. Holes were everywhere I looked, a stark reminder of the city’s recent past.

Political displays.

Across from my own bullet scarred apartment, is a shell of a building which I was able to at last find out about by asking Emina, my guide for a day trip to Tjentiste spomenik. It turns out the building is owned by someone from out of town who hasn’t decided what to do with it. so it just sits there, adjacent to a very contemporary building, part café part business; the contemporary design features perforated square shapes and I wonder if this was a Post-modern reference to the bullet holes in the rest of the town; I hope that the town does not try to erase these scars as they are a poignant reminder of the past, however, for those who live here, they may wish to forget.

Back view of building partially demolished during the siege.

A Sarajevo Rose or crater from the siege filled with red paint as a reminder.

Detail of building from Sniper's Alley.

For Emina, her experience of the war has influenced her outlook on life and for her, to not be afraid of danger. In fact, she seems to find life boring if there isn’t an element of danger, hence her chain smoking, risky driving and preference for dangerous sports. For many of her peers however, the experience had a more detrimental effect. ‘Many of my friends are in hospital’ she offered; ‘mental health issues?’ I probed. ‘yes'. She was a 12 year old during the war; I wondered how this experience has affected the outlook on life for other 'Miss Sarajevos'.

Create Your Own Website With Webador