I heart I heart Chisinau sign with the Presidential Palace in background sign with the Presidential Palace in background, Moldova.

In 2022, when the world was taking baby steps returning to travel after the Covid Pandemic, I was ready to go and Moldova had been on my itinerary. Then in February, Russia declared war on The Ukraine and travellers down south abandoned any thought of traveling to Europe. If you look on the map, you can see Moldova nestled between The Ukraine in the east and Romania in the west and if that’s not a deterrent enough, there’s Transnistria, a breakaway region and disputed territory of Moldova which borders The Ukraine. With only two months to finalise my plans, I decided that 2022 might not be the best year to visit Moldova (and its neighbour, Romania). It seemed that most Australians avoided Europe in 2022, mainly because of the fear of catching covid overseas; adding a war, which the media were suggesting could turn into a world war, dumped travel into the ‘too hard’ basket for most. Sadly, 2023 has not brought an end to the war, but for most of Europe, the citizens are trying to get on with life with many neighbouring countries supporting the Ukraine as much as possible. At the time of writing, the war seems to be centralised in areas of The Ukraine and neighbouring countries have lost income from tourism. This was already apparent in 2022. For example, when traveling through Cyprus I asked a waitress in Kakopetria if the town was usually this quiet. She mentioned that most of the tourists were usually from Russia or the Ukraine, so Cyprus has lost a significant amount of tourism. I hadn’t even considered that Cyprus would be a hot-spot for these countries, but everyone likes to holiday so why not? Finally, in 2023, and after having already visited six other countries in the one trip (not to mention a Pacific sojourn in January), I arrive at Chisinau, the capital of Moldova. Getting there was pretty easy if you are coming from Yerevan, Armenia, as I was. In fact, I was surprised, when researching direct flights, that many to Romania fly via Chisinau, despite it being smaller than Romania’s major cities. My apartment host Vlad had offered to collect me from the airport for around 10 euros which, although more expensive than public transport, seemed convenient. He also helped me get a sim and top it up which is always a relief. The upstairs apartment, like so many I have seen in former soviet countries was fairly plain on the outside but modernised on the inside, but each external door had a different design, maybe to make it easier to recognise your own apartment in the absence of numbers. I found this out when I returned to the apartment after visiting the supermarket around the corner. I used the code to enter the main door, then ascended the stairs to Room 15. I recognised the distinctive door design, turned the key, walked in. The apartment was different! There were people inside watching TV! I closed the door in horror and messaged my host. Fortunately, Vlad was able to return to assist me and point out that I had in fact entered the wrong building! I can only think that both the main door and the door of the family who I nearly visited had not been locked properly at the time and I wondered if I was the only one who had ever entered the wrong building before. Chisinau is often touted as: · The most boring European capital · The worst European capital · The least visited European capital Writers and bloggers are quite comfortable talking in depreciating terms when describing Chisinau and Moldova: ‘Home to some 700,000 inhabitants, Moldova’s capital, Chisinau, may not be the most aesthetically pleasing of European capitals, but its unique mix of brutalist architecture, modern high-rises and plenty of green space give it a charm of its own.’[1] Before my arrival in Chisinau, I had conjured images in my mind of a third world town with primitive means of transport, old rusty trams rattling by, low infrastructure, and grey soulless architecture (even though I like grey Brutalist architecture). Instead, I was presented with museums, lush green parks, live music, mosaics, architectural diversity including some late 20th century Modernist and Brutalist gems alongside ornate Orthodox churches, national pride, dancing, and wine, wine, wine. In 2021, Moldova featured in the top 10 countries in the world for export of wine. This fun infographic (apologies, non Facebookers) shows how wine exports have changed since the 1960s. Yes, Australians, we’re up there. Moldova’s exports have dropped somewhat in the past two years but it’s still high around 21st in the world. And wine is very important to the economy: ‘The Republic of Moldova boasts a very dynamic wine industry, broadening still further the gap between perception and reality. Whereas in many countries, wine flirts or even overtly indulges in luxury, here most of the population makes a living out of it.’[2] in my four days in Chisinau I did not visit the famous Cricova underground cellar but I was fortunate that my time coincided with a wine festival. For around $20AUD, I received a detachable card enabling me 10 wine tastings. Fortunately this was able to be spread over the two days of the festival, otherwise I would have been (even more) tipsy. Although Moldova is more renowned for its white wine, the light reds were what impressed me. After one tasting, I enquired as to how much a bottle would cost and the seller rolled his eyes and dryly answered ‘Around 5 euros’ as if to say ‘more than you can afford, lady’. At around $8AUD this would have been quite the bargain for this Aussie. Perhaps Australia should start importing from Moldova. I did find it hard to break into conversations at the festival until a man came rushing up to me and garbled something I couldn’t understand. I did the usual, informing me that I could only speak English. ‘Phot me’ he urged, pointing to his phone. I immediately understood the request and ‘photted’ him with the festival background. Then I gestured that he could return the favour and do the same for me. I now have a ‘phot’ of myself enjoying the festival. I’m not sure if it was part of culture or if I just struck a particularly festive weekend, but I experienced outdoors music everywhere, from traditional songs in the park to which people either waltzed or did some sort of Zorba the Greek dance, through to various styles of contemporary music at the wine festival.

Yours truly participating in the cultural pride of the country: wine.

One may think that not having the best spatial awareness is a disadvantage for a solo traveller, but I find that it always takes me to interesting places I would not have thought of otherwise. This occurred one day, when despite my best planning, I caught the bus on the wrong side of the road. As I (acting casual as I got off at the next stop), looked up, I saw a fabulous mix of architectural styles, monuments and buildings. The Cosmos Hotel is a late 20th century hotel building with a distinctive façade that includes wave like balconies. It is situated at a major intersection with includes a public square dominated by equestrian statue with the figure Grigory Ivanovich Kotovski (1881-1925), a polarising Communist/ Boshevik hero. The statue has been somewhat romanticised given that the armies at the time did not use horses!

The Cosmos Hotel, built 1983.

Near the Cosmos Hotel.

Built between 1974 and 1983 and funded by the Labor Unions of the Republic of Moldova, the hotel was once a popular destination during Soviet-era summer holidays, when travel beyond the Union’s borders was restricted. Following the dissolution of the USSR in the 1990s, bookings declined and parts of the building were repurposed as office space. Like many examples of Communist-era architecture, the Cosmos Hotel possesses a striking and distinctive aesthetic, though its interior now requires significant restoration to be functional once more. With growing interest from architectural associations and preservation archives, I hope that tourism in this region will increasingly recognise the cultural value of these post-Soviet structures, not just the pre-1950s “traditional” styles that tend to dominate travel itineraries.

A closer view of Grigory Ivanovich Kotovski, who in fact did not ride horses at all.

Nearby stood the Logos Publishing House, a striking example of late-Soviet geometric design. Its façade features a grid of compact balconies, many now hosting air conditioners instead of readers enjoying the view. The diagonally staggered arrangement gives the building a sense of movement and rhythm that enlivens its concrete surface. Later I discovered documentation highlighting its architectural significance, confirming that this was more than just an intriguing curiosity from a bygone era.

Logos Publishing House built in 1980.

Chisinau is full of history told through its figurative monuments, each a fragment of the city’s complex past. Just around the corner from the apartment where I was staying stood the Monument to the Heroes of Komsomol, a Soviet-era landmark completed in 1959 that anchors the boulevard between two main streets. The Komsomol, officially known as the All-Union Leninist Young Communist League, was founded in 1918 as the youth wing of the Communist Party. At its centre, a bronze female figure raises a torch in triumph, symbolising victory, while below her a group of five sculptures represents the courage and dedication of Soviet youth. Although membership was nominally voluntary, those who did not join often faced limited opportunities for education or travel. Paradoxically, for many women, joining the Komsomol offered a rare path beyond the boundaries of domestic life, granting access to study and public participation.

Monument to the Heroes: Komosol, built in 1959.

One advantage of Moldova’s relatively small size as a capital is that most of the sites are walking distance, especially from my relatively centrally located apartment. Past the Komosol monument, architecture enthusiasts are spoilt for choice and with each building telling a story of the history usually of the past 100 years or pre- and post-soviet era. One building that stood out to me because of its height and unique design is the Presidential Place. It joined many other government and buildings and theatres along the main boulevard.

The Presidential Palace building.

The Presidential Palace was built between 1984 and 1987 on the site of a German Lutheran Church dating back to the 1830s. It was made to be the new building of the Supreme Soviet of the Moldavian SSR. After Moldova gained its independence, the building became the residence of the president of Moldova starting in 2001 with President Vladimir Voronin. The building was badly damaged during protests on April 7, 2009 against President Voronin. As a result of the protest, the palace was closed off. With financial assistance from Turkey, the palace was renovated and re-opened in 2018. After the renovations, President Dodon joked: "There was nothing here when we arrived, but you know, I’m a man who treasures his household, so we brought a few things". [3]Under his term, he kept created wine basement, an artificial lake, and a chicken farm. His presidency also included the introduction of a Ziua Ușilor Deschise (Open Doors Day) at the palace for Moldovan youth.

Parliament of the Republic of Moldova.

Across the road from the Presidential Palace stands the Parliament of the Republic of Moldova, a proud creation of the late 1970s. Built between 1976 and 1979 by architects Alexandru Cerdanțev and Grigore Bosenco, it was originally the headquarters of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic. The building’s open-book design might seem like a clever wink to enlightenment, though the irony is hard to miss given the period it represents.

Entirely poured in reinforced concrete with a granite façade, it is a model of Soviet-era precision and order. Above the central entrance, the institution’s name, Parliament of the Republic of Moldova, is neatly cast in metal, leaving no ambiguity about who is in charge. Inside, the offices occupy one side while the main parliamentary chamber takes the other, a layout that feels both practical and ceremonial.

Today, the building is recognised as a monument of national importance and forms part of a complex covering about ten thousand square metres. The foreground garden, with its colourful topiary and cheerful sans serif letters spelling MOLDOVA, brings an unexpectedly playful touch to the otherwise austere geometry of the structure.

Government Garage with some Brutalist artistic license!

Not on the main boulevard but just around the corner, I came across another fine example of late Soviet architecture in the Government Garage. It is one of those buildings that catches the eye with its bold lines and unapologetic use of concrete. A star of Brutalist social media sites such as Socialist Modernism, it has become something of a cult favourite among admirers of this architectural style. Despite its online fame, the only information I was able to find was that it was designed in 1978 by architect Anatoly Dubrovsky.

More views of the Brutalist Government Garage.

It quickly became apparent that the city had an unspoken zoning plan: government buildings on one side, arts buildings on the other, and theatres seemingly wherever they fancied. Unlike in Australia, the entrances in Moldova were often cryptic, and signage could be found nowhere near the actual door. After some determined wandering, I finally located the doors only to discover that both the main museum and art gallery were closed on a Friday. A little later, internet sleuthing revealed the reason: it was a public holiday. The attendants had not mentioned this, simply stating that it was closed, but really, how could I blame them for assuming I knew or for their limited English?

Saturday, however, brought redemption. I finally made it inside both museums. The National Museum of Ethnography and Natural History immediately stood out, its architecture a world apart from the post-Soviet blocks nearby, a clue to its 1905 origins. Its story stretches back even further, to 1889, when the Zemstva of Bessarabia organized the first Agricultural and Industrial Exhibition, laying the foundation for what would become Moldova’s oldest museum. Over the years, its name may have changed, but its treasures remain steadfast: today, some 135,000 exhibits chronicle the nation’s rich heritage.

The oriental style facade of the Museum of Ethnography.

The permanent exhibition operates under the title “Nature. Human. Culture” with an area of over 2000 m2. The museum also has a Temporary Exhibition Hall, in which numerous seminars, master classes and exhibitions take place, both from its own heritage and from the heritage of other local museums and from abroad. The exhibitions of handicrafts have become traditional and are organized every year.

Interior of The National Museum of Ethnography and Natural History.

Folklore events, national and international competitions and festivals are regularly held in the museum, showcasing folk creations from all over the country. Outside the museum there is also a Botanical Garden with a Vivarium, which gathers the most widespread species of plants, trees and shrubs from the Republic of Moldova, as well as exotic birds, reptiles and fish. The Museum building was designed by architect V.N. Tiganco.

Ever get the feeling you're being watched? Wax figures wearing traditional costumes in the The National Museum of Ethnography and Natural History.

Cutaway section of a chicken showing its skeleton at The National Museum of Ethnography and Natural History.

One of the wild boars that I was often warned about on hikes in The National Museum of Ethnography and Natural History; I loved the painted backdrops.

Peppered between the city’s buildings are countless parks offering pockets of calm amid the bustle. I took a bus further afield to Valea Morilor Park, a beautiful, much-loved lake and forest retreat. The lake, once known as Komsomolist Lake when it was created in 1952, is entirely artificial (see my comments on the Komsomolist Monument), but its modern name translates to “Valley of Mills” in Moldovan and Romanian.

The park is best known for its grand Cascade Stairs, which reportedly outnumber even the famed Potemkin Stairs in Odessa. During Soviet times, the area was a hub for sporting events. When I visited, I followed the sound of distant music, assuming a festival was underway, only to stumble upon a children’s talent quest , tiny performers singing and dancing to pop hits, reminsicent of the film Little Miss Sunshine.

Continuing around the lake, I was delighted to find a stretch of forest, a welcome burst of shade after days in the city. Wandering further, I slipped through some bushes and an open fence toward an intriguing, if neglected, monument. Hidden behind the ornate Madison Park banquet hall stands a relic of another era: statues of Lenin and Karl Marx, survivors of the Communist past.

Originally erected in 1949 outside the Government House, the statue was dismantled and relocated after 1991. Why it ended up here remains something of a mystery.

Cascade fountain at Valea Morilor Park.

Cascade fountain at Valea Morilor Park.

Bathers at the artificial 'beach' at Valea Morilor Park.

Forest hiking trail at Valea Morilor Park.

Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin and Georgi Dimitrov (cropped out) monument.

Chisinau is fortunate to be able to still boast a good range of rare and (in my opinion) beautiful mosaics from the soviet era. At first glance, the message of The City is Flourishing and Being Built at the Chisinau bus station is unambiguous. Designed by Mikhail Burya and Vladislav Obukh and completed in 1974, the spectacularly detailed mural shows figurative subject matter engaged in family activities music and curiously, a female figure appears to stand on a balcony, in Shakespeare’s Juliet style (just my interpretation!) against a background of high rises.

The City is Flourishing and Being Built mosaic, 1974.

Mosaic upstairs at the Chisinau bus station.

Continuing from the mosaics at the bus station, another fine example of Chisinau’s Soviet-era artistry can be found in a nearby park: the Stone Flower Mosaic fountain, designed by Alexander Kuzmin. Its subject matter is more general, but no less striking. The water may no longer flow, and a person of my height has to balance on tiptoe to peek inside, yet it remains a textbook example of 1980s mosaic fountains. Sadly, modern graffiti artists seem to regard any patch of concrete as fair game, oblivious to the fountain’s quiet status as a cultural relic.

Stone Flower Mosaic.

Stone Flower Mosaic interior.

Hotel Turist in Chișinău is a representative example of late Soviet modernist architecture, built around 1971 under the design of Roman Bekesevich.

Winds-Waves, House of Writers Mosaic, 1974, designed by Aurel David.

After a morning spent exploring Chisinau’s mosaics and architecture, I caught a bus to the Eternity Memorial Complex, a striking monument dedicated to Soviet soldiers who died fighting German-Romanian troops during the Second World War. To reach it, I walked through a cemetery, an atmospheric approach made slightly less serene by three rather savage dogs who seemed to be guarding a particular grave. Whether they were protecting it out of loyalty or habit, I wasn’t about to get close enough to find out.

Tombstones near Eternity Memorial Complex Monument.

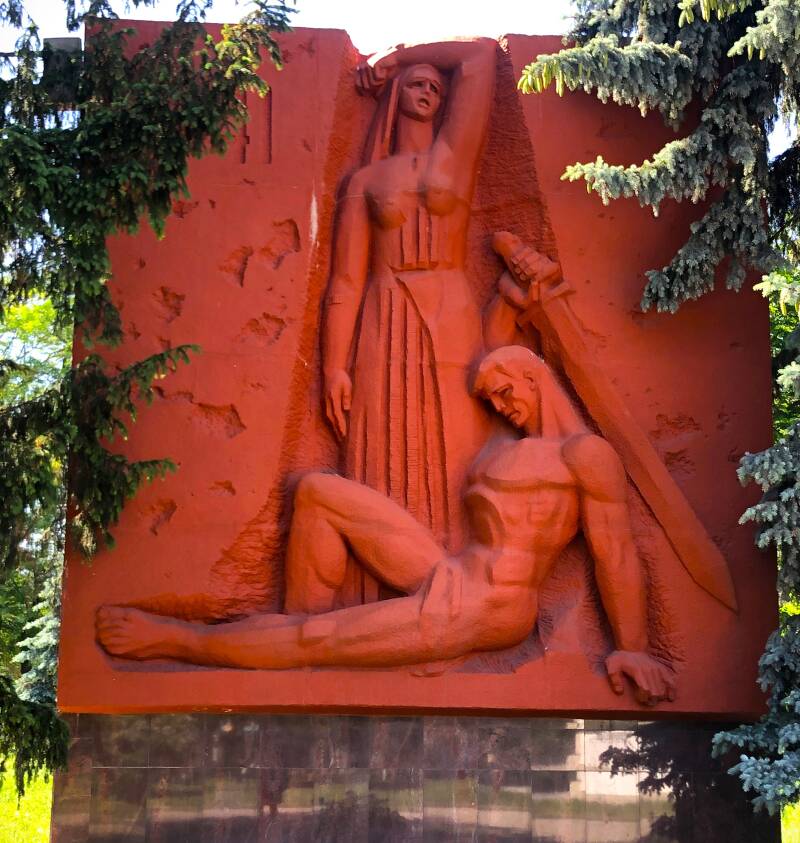

After making my way through the cemetery, I reached the Eternity Memorial Complex, built in honour of the Soviet soldiers who died in the Great Patriotic War. Restored on August 24, 2006, to mark the 62nd anniversary of Moldova’s liberation, the monument’s centrepiece is an arresting formation of five 25-metre stone rifles rising together in the shape of a pyramid. The entire complex is strikingly red, the colour coming from the stone used to create the bas-relief sculptures that depict the stages of the Soviet victory in World War II. The vivid tone was chosen to symbolise the heroism, sacrifice, and dynamic progress of the Red Army soldiers commemorated here. At its heart burns an eternal flame set within a five-pointed star, watched over by an honour guard from the Moldovan Army who change hourly. Wreath-laying ceremonies are still held at the site on national holidays.

Eternity Memorial Complex Monument.

One of the many friezes that lead up to the Eternity Memorial Complex monument.

After spending time admiring Chisinau’s bold Brutalist architecture and late 20th-century mosaics, visiting the Church of Saint Pantaleon felt like stepping into another world entirely. Built in 1891 and designed by architect Nikola Ziko, this Greek Orthodox church is a fine example of Greek Byzantine architecture, full of elegant arches, ornate detailing, and soft, harmonious lines. Inside, it houses the “Throne of Panteleimon the Healer,” a tribute to the saint to whom the church is dedicated, one of the 14 Holy Helpers and the patron saint of physicians and midwives. Its pastel tones and golden domes radiate warmth and serenity, a striking contrast to the grey concrete and angular forms of Chisinau’s Brutalist landmarks. Where the Soviet-era monuments project power, progress, and ideology, Saint Pantaleon speaks of faith, compassion, and continuity, a gentle counterpoint to the city’s modernist legacy.

Church of Saint Pantaleon, front view.

Church of Saint Pantaleon.

I only spent four days in Chisinau before taking a bus to Bucharest, Romania and even in that short time the city left a strong impression. I missed a few Brutalist icons such as the State Circus and the Romanita Housing Building, and I didn’t make it to the famous Cricova Underground Cellars, yet I still felt immersed in so much of what Moldova has to offer. Chisinau’s blend of striking Soviet-era architecture, graceful churches, and leafy parks gives it a character unlike anywhere else in Europe. I spent very little, always felt safe, and left feeling inspired to return. For anyone planning a European trip, Moldova deserves a place on the itinerary; it is one of the continent’s most underrated destinations, especially for those who love architecture (and wine!) and discovering places that still feel authentic.

Coarsely finished rendering is contrasted with delightful mosaics adorining apartment buildings.

Resources:

https://socialistmodernism.com/the-cosmos-hotel-chisinau/

https://www.itinari.com/hotel-cosmos-the-ussr-patrimony-in-the-heart-of-chisinau-dxhz

https://jes.utm.md/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2021/04/JES-1-2021_91-99.pdf (about government buildings)

https://edition.cnn.com/style/article/soviet-architectural-legacy/index.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Komsomol

https://www.kathmanduandbeyond.com/winds-waves-house-writers-chisinau-moldova/

NECSUTU, Madalin Brutalist Architecture meets old world charm in Chisinau Balkan Insight 2028

SCAVO, Julia The Moldovan wine industry gears up for exports Gilbert Gailard May, 2023

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Presidential_Palace,_Chi%C8%99in%C4%83u#cite_note-11 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Presidential_Palace,_Chi%C8%99in%C4%83u#cite_note-12

Create Your Own Website With Webador